The role of role models in closing the wage gap

Estimated reading time: 7 minutes

Closing the wage gap is an ambitious and vital goal. We post, like and retweet the #PAYMEs and know your worth, then add taxes, because they bring to the mainstream an important issue affecting over half of the world’s population. But, why is a pay gap still happening? In 2020?

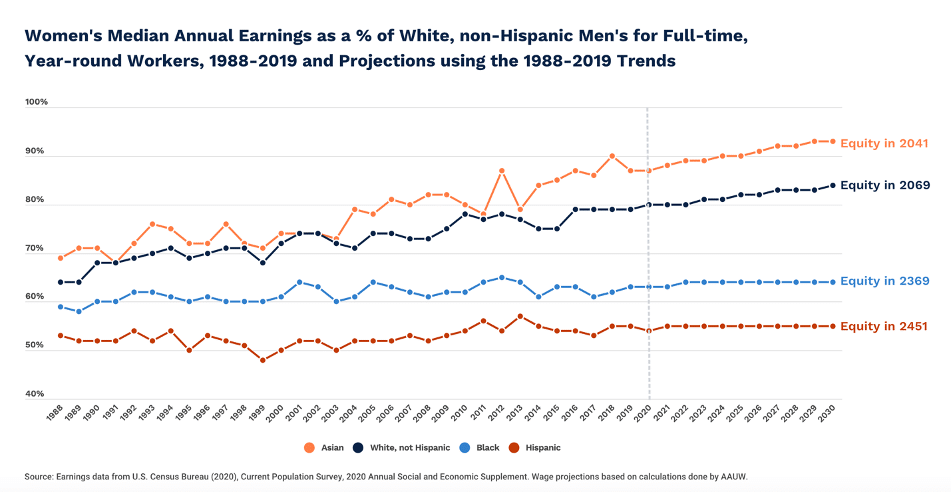

Let’s focus on the gap here in the US. According to the AAUW’s “Simple Truth About the Gender Pay Gap,” women working full-time in the US are paid 82 cents to every dollar earned by men. As we know, this pay gap, over time, amounts to thousands, even millions of missed lifetime earnings. The trend continues on into retirement. Lower earnings translate to smaller Social Security benefits and women having roughly 70% of the overall retirement income that men have. Recent reports are positive in saying that the gap is slowly reducing, however based on projections, women still won’t see true gender equity for generations:

Seriously, why is there a wage gap (also, sorry, MBAs)

So we go back to that first question we asked: why does a gap in pay even exist?

Women outpace men in higher education, certainly receiving the schooling and certifications needed to succeed, so why isn’t that accompanied by salaries that close the gap (and perhaps even reverse it?). Not to rub salt into a wound, but as women inch closer to parity in business school, an even wider pay gap exists for MBA graduates.

“The largest uncontrolled gender pay gap is for those with MBAs. Women with MBAs take home $0.75 for every dollar men with MBAs take home. The gap decreases to $0.97 when we look at the controlled pay gap, suggesting that women and men with MBAs have very different job titles and job levels. These findings might be indicative of highly educated women taking jobs that are less demanding and therefore less rewarding than their educations may have prepared them for, possibly because of family considerations. However, it may also be indicative of the motherhood penalty or more general bias against highly educated women or women in particular occupations or industries.”

Why?

This is something we’ve considered a lot here… the question we have always asked is: what is it about my having *just* invested [hundreds of] thousands of dollars into my education and my professional growth and development that is signaling to employers that I’m ready to somehow take my foot *off* of the gas pedal?

For many of us, it doesn’t add up.

A recent study published by Professors Aradhna Krishna and Yeşim Orhun at the Michigan Ross School of Business looks at why “Gender (Still) Matters in Business School.” Considering their findings and conclusions around gender gaps in undergraduate business school performance, as well as that point about the controlled pay gap, we can make some connections and potentially start solutioning at the undergraduate level – well before the individual pay gap really catches on.

The “Pipeline”

We talk a lot about the importance of women having P&L ownership and how that leads to women taking on the C-suite roles that really drive a business forward. (They do the mo$t in truly closing the wage gap.) “Business schools train the talent that fuel most of the management jobs. Even though business schools in the U.S. boast a 43%–47% of female student representation according to the Department of Education (2018), if female students are not successful in the academic paths that lead to more lucrative career options, the pipeline issue cannot be fixed.”

Krishna and Orhun dig into the disconnect and how it seems to start as early as our college years. They studied a top undergraduate business school in the Midwest, analyzing student performance and feedback (from numerous angles) between Fall 2006 and Fall 2017 to investigate the question: “Why is there gender imbalance in the business fields where it exists, and how can it be changed?”

The Research

Krishna and Orhun considered three potential drivers of gender performance differences (GPD) that prevent us from closing the wage gap. Two of their three hypotheses were based on gender stereotypes. The last started to explore potential innate differences across genders.

- Hypothesis 1: that GPD may arise from gender stereotypes held by students (which influence student expectations of their likely performance in different courses; “stereotype bias”)

- H2: that GPD may arise from gender stereotypes held by instructors (which influence student performance through instructor behaviors, expectations, and evaluations; “instructor bias”)

- H3: that GPD may be related to innate differences in interest across genders (the idea that “women aren’t interested in finance“)

They found “stereotype bias” to be the only real driver present in this study.

On average, in quantitative courses, female students lag behind male students. They score 11% of a standard deviation lower than male students who are academically and demographically similar. (The opposite is true in non-quantitative courses, where female students score 22% of a standard deviation higher.) Why the difference?

On Role Models

Krishna and Orhun found that “female students who have a mid to high aptitude for quantitative subjects are the most disadvantaged by gender stereotypes and benefit the most from role models. It is disconcerting that the professional world is missing out on these women, due to the misallocation of talent, driven by such stereotyped beliefs.”

Yep.

They found that female students do better and achieve higher grades in quant courses. Performance improves by 7.7% of a standard deviation when taught by female instructors. (Instructor gender has no material impact on grades of male students.) Basically, seeing and learning from successful women in finance and other quantitative spaces is meaningful.

Role models in these spaces inspire female undergrads to achieve higher grades and pursue quant-heavy fields; the ones that are more lucrative and generate higher lifetime earnings. The ones that do the most in closing the wage gap.

Representation DOES matter

Krishna and Orhun say assigning more female instructors could help eliminate the gender discrepancy in quantitative course grades. “Business school administrators can help align female students’ abilities more accurately with their educational choices by assigning more female instructors to teach quantitative courses.” This is when we hear in our minds the phrase: representation matters.

They point out the “lopsided distribution of female instructors across subjects… 17% of students are taught business economics by female instructors. In contrast, 43%, 31%, 68%, and 85% of students are taught marketing, management and organizations, business law, and strategy, respectively, by female instructors.” Though women continue to go to school and pursue advanced degrees [and business schools keep moving closer to gender parity across programs], “women are underrepresented among students taking jobs in investment banking (20%) and overrepresented in accounting (65%) and human resources (90%).”

Ultimately, reducing or eliminating gender performance differences in quantitative courses could point more talented women toward more quantitative and more lucrative careers.

It’s not just asking for more

The combination of more female role models and a shift towards quantitative fields can help even out the overall gender pay gap. The pool of female instructors teaching quantitative courses might not be immediately available, but the university setting allows for all sorts of interactions and inspiration through student organizations, speakers, alumni connections and more. This study focuses on student performance and feedback at the undergraduate level, however it’s not difficult to extend these findings and conclusions to the graduate business school classroom.

Take a look at that controlled pay gap mentioned earlier. When comparing men and women in the same roles and industries, the controlled MBA pay gap is only about 3%. But looking across the entire MBA cohort, the overall gender pay gap is 25% (the largest uncontrolled pay gap); even in those first post-MBA jobs. That stat suggests job titles and roles differed; this study helps further understand why they differ. Not as many women are headed into the quantitative roles that garner more money over the course of a career.

It’s on all of us

Telling women to get that money and ask for more is absolutely worthy advice. However, we know it’s not entirely on women to close the wage gap during salary negotiations. This study does uncover another lever available to us in supporting female students in the pursuit of gender equality.

It’s also about helping women pursue their full potential. The Professors say “our economy is only as strong as the talent that fuels it.” It’s on all of us to strive for better for everyone.

Share with us

Did you have a female professor who inspired you to pursue a quantitative career? Would love to know more about the role models who inspired you and impacted the course of your career.

Want to share your research with us or contribute to MBAchic with your own experiences? Let’s talk.

Images from PxHere and MBAchic